Stories

The Last Breath

by Liam Hogan

“When I’d seen her, sixty years earlier, she’d been no rainbow, sure, but the edges of her scales had still glimmered with colour.”

“When I’d seen her, sixty years earlier, she’d been no rainbow, sure, but the edges of her scales had still glimmered with colour.”

You don’t get to the age of two hundred and seventy-eight by being stupid. Or careless. Or, worst of all, trusting. Yet there I was, trapped and shackled by dragon iron. The accursed chains were as ancient as I was, the skills of their forging lost in the great wars, but they were as unbreakable as ever. It was best to conserve my strength; so, thoroughly annoyed with myself, I lay on the dark cavern floor, legs stretched before me and my head resting on them, waiting for whatever came next.

Whatever came next was a flashily dressed royal-type. Hopes rose. Kings and princes were, in my experience, vain creatures, easily flattered and bargained with and most of them quite short-lived — relatively speaking. There would, I was sure, be an out, even if I had to outlive him to get to it.

He halted at the far reaches of the dreary subterranean void, a distant, insignificant figure, well out of reach of my constrained claws. Possibly not out of reach of my tail, though it would require an impressive back flip to whip it that far in his direction. Nor, I supposed, would he entirely escape the extremities of my fiery breath. I could, at the very least, singe this arrogant human’s neat beard. Though that was definitely a last resort.

“Dragon,” he said, the feeble sound lost in the vast space.

“Count the limbs,” I growled, “It’s wyvern, Prince.” Wyverns — and dragons — have deep, gravelly voices. It comes from the heavy smoking.

“And it’s King, not prince,” he said, with a degree of hauteur that he must have practised in front of a full-length mirror. “King Ulfred.”

He was young to be a king, no more than three decades. I had half a mind to ask who he’d bumped off to ascend to the throne, but like I said, royal types can be awfully short lived. Especially if they’re stupid, or careless, or trusting. I didn’t want to antagonise him too much; just enough to show I wasn’t cowed.

“You all look the same to me,” I yawned, and there was a yelp from the man-at-arms trapped beneath my claw.

The King’s eyes widened. “Is that man still alive?”

“Yes.”

“May I ask… why?”

“I thought he might be important to you. Call him a peace offering, if you will.” I smiled, all teeth. “A sign of good intentions.”

The King didn’t smile in reply. I could have warned him: it ages you, maintaining such a severe expression. Well, it ages humans.

“The men were picked to be disposable.”

“That explains the laughably thin armour.”

He shook his head. “They were nothing more than a distraction, while my elite guard approached with the restraints. He means nothing to me. Do with him as you will.”

There was a whimper from beneath me. The man had been admirably still, no trouble at all, albeit under the threat of a very messy death. It would be wrong to say I felt anything for him, any more than the King would for a chicken destined for his table. And yet…

“I don’t much like canned food,” I quipped, though the quip would fail to land for a good number of centuries. I lifted my claw and prodded the prone man into action. He stumbled to his feet and fled — away from my wickedly sharp talons, and away from his uncaring King, deeper into the cavern where less frequently glimpsed dangers lurked. You try to do a good deed…

“What is it you want from me, King Ulfred?”

“I’m at war, with King Francisco—”

“If I could stop you right there.” Like I said, we have deep voices, it’s easy to talk over someone when they’re just a leaf rustling in the wind. “You want to use me as a weapon?”

“Well, yes.”

“What makes you think I’ll let you?”

He finally smiled; I preferred the frown. “I’ll only release your chains, not the shackles. You want out of those, you do exactly as I say.”

Cunning. And dastardly. Like sharks and crocodiles, wyverns never stop growing. Imprisoned by dragon iron, my limbs would be crippled over time. A slow, painful future.

I peered down my nose. “You might make me promise, instead?”

“And that would hold you?” The frown was back.

“A wyvern’s promise is far more binding than iron, King Ulfred, even dragon iron. As I’m sure your advisors told you. Or perhaps you don’t listen to them, hmm? Anyway, you’re barking up the wrong tree.”

“Oh? Am I?”

“Yes, if you want a weapon, you want the biggest, baddest flying monster you can find. And that’s not me. What you need is an ash wyvern.”

“An ash wyvern? I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

“Oh, they’re very rare. Hardly surprising you don’t know about them in these blighted backwaters.” I watched, delighted, as he bristled. Such thin skins, humans. “Most who encounter them don’t live to tell the tale. But the tale is worth telling.

“An ash wyvern is larger than I am, and, as you might guess from the name, they’re silvery-white and appear as ghosts. But its their breath that makes them unique, and uniquely feared. They have the most destructive, fiery breath in the world. A breath that brings death, far more so than any mere dragon or lesser wyvern like me. It is a breath that melts stone, that eats through metal like a hot knife through butter. As for what it does to flesh, well, you can imagine. Most of all, it is a breath that, once unleashed, cannot be restrained. It consumes everything in its path, until all is laid to waste for leagues around, ash and dust, even the wyvern who breathed it.”

King Ulfred stroked that neat beard of his. “A mighty weapon, then. But one that can only be used once?”

“Trust me, once is too many times. You never actually want to deploy an ash wyvern! Genies out of bottles and all.” I wasn’t sure he’d get that reference either. Not an anachronism this time, more a whole other mythology. “Me, I can swoop down and kill a half dozen soldiers in each pass, though it’s the scare factor that gets enemy cavalry all riled up and sends unwashed rabble scurrying for cover. But an ash wyvern…” I shook my head ponderously. “Once it is unleashed there won’t be anything left that didn’t have the foresight to crawl under a very large rock. No crops, no forests, no livestock, no army or farmers, no castles and certainly no rival king. All wiped from the face of this Earth. Ultimate destruction from the ultimate weapon.”

It was quite horrid, how his eyes glittered as he listened. “So,” I pointed out, feeling the need to join the dots, “just the fact you have one, will guarantee you victory. The scare factor. Because against such a terrible threat, only a fool would attempt to stand.”

“And you tell me this, because?”

“Because, in return for my freedom, I can get you an ash wyvern.”

“Indeed? Very well. But the same rules apply. I won’t release your shackles, just your chains. And you must swear—”

Here it came…

And then it didn’t.

Perhaps he had heard of genies after all. Or other magical beings, whose words were like the reflections of the moon on a cold pond. Deceptive, and impossible to grasp. This was the point at which he could have done with those neglected advisors. In the end, he didn’t do too badly. Perhaps I underestimated him.

“You must promise,” he finally said with infinite care, “Not to cause me harm, directly or indirectly, to the best of your abilities. You must promise to bring me an ash wyvern. And…”

It’s always the third bite at the thorax, isn’t it?

“…you will only be freed once victory is mine!”

“I don’t see how I can promise the last part, since that is in your hands,” I said, deflating his triumph.

“Well…” He looked confused; perhaps I had overestimated him. “Then promise the first two parts, and I’ll look after the third.”

I promised, reluctantly, and the chains (but not the shackles) were released. I grinned my most evil grin and ducked my head sharply towards the king, who was now very much in range. “Say,” I said, and he squealed and fell over backwards as his royal guards scrabbled for their swords and spears. “You don’t have a history of heart problems in your family, do you?”

He shook his head, unable to speak, or even squeak.

“Well, that’s good,” I said. “It’s hard to keep my oath if I don’t have a full medical history, if I don’t know how sensitive you might be to shocks and scares and the like. To the best of my abilities, right?”

With that, I squeezed up the narrow crevice to the outside. Thankfully, it was daylight, a wan sun working away at the morning’s mist, just enough to warm my wings. There was a gathering of the King’s men watching as I stretched, shaking the water and fallen dirt from my back. I thought of snatching a few — travelling snacks for my journey — but concluded that this might indirectly harm the King. Pesky thing, promises.

It was good to be in the skies again, even though I wasn’t entirely sure where I was headed. North, was my best guess. If it hadn’t been for the shackles around my ankles and the irksome promise, I’d just keep going. Find somewhere with no dratted Kings, no dragon iron, maybe no people at all. Not that there were many places like that any more. The Earth was getting awfully crowded, and the humans I did encounter never seemed happy to see me. Can’t understand why. I preferred their cattle to their children, or their women. The older the better — richer flavour and more to chew on. And yes, I’m still talking about cows.

I stopped to ask the way from a sun-basking griffin. She couldn’t help smirking as she glanced at the bands of dragon iron, my twin badges of disgrace, and I’d have clipped her wings if she hadn’t given me such promising directions.

The way was up into the hills, low cousins to the mountains that crowded the horizon, wearing capes of snow that never melted. Well, not for the next half a millennia or so. A wyvern’s ability to glimpse the distant future meant that things that seemed constant weren’t, and things you keep expecting to change, don’t. Or not in the ways you expect. There’s a certain circular inevitability to history, to stupidity, and yes, to war.

The abyss the griffin had guided me to, at the far end of a dark lake, was suitably ominous. A cleft in the hillside, a stream trickling from its mouth, a fetid smell wafting from its depths… Even I had a shudder of apprehension as I entered the foreboding ravine, wriggling my way until I came to a pitch-black chamber, where I had the sense of being minutely inspected.

“Hello, younger brother.” A voice as ancient as the rocks sighed.

“Altran; thought I might find you here. Kin. Sister. Friend?”

“I see you got yourself captured.”

“Ah, yes. Though how can you…?”

“I can taste the iron, Shurni. Not just any old iron, either. Dragon iron. Haven’t smelled that sour stench for over a century. Chaffs, I’ll bet? Someone must really want you to do something for them.”

“Well… they did.”

“Oh?”

“And now they want you to do something for them.”

“ME?!” the voice thundered, rocks rattling from the roof, and I had a grim vision of the two of us buried forever beneath that lonely hill. In better news, the rumble let a thin sliver of light creep into the Stygian depths. In worse news, the light revealed the remains of what Altran had been surviving on while she wallowed in her misery, the discarded bones and tattered fleeces of snow-blind sheep and scraped goats that had strayed into these tunnels. It explained the crunch underfoot. Amazing she could pick out cold iron over all of that. I suppose she must have gotten used to it, though heavens knew how.

“Yes,” I said. “You, sister. I need you.”

“For what?” Her measured reply was far more dangerous than her exclamations. She was from a clutch two centuries older than mine, and that was why I’d appended the hopeful “friend?”. We might be related, but we didn’t grow up together. My plan — such that it was — relied on her willing cooperation. As did my life.

“I want you to join an army.”

You could hear solitary drips of water pinking into some pool somewhere. I held my breath. The hillside held it’s breath. Even Altran was very, very still.

“What sort of an army?”

“A… human one?”

“Have a care, brother!”

“You won’t be asked to do anything!” I protested. “Just to be seen!”

“Just, my inane little brother says. Just be seen. I should have crushed your entire clutch when I heard mother was laying again!”

“Well, that’s—”

“Look then — look, if you must!”

She reared forward and into the tendrils of light from above. Altran’s entire head was bone white. Colourless, other than the two spots of blood red that flashed in her furious eyes.

That’s the problem with fire breathing, for wyverns. Dragons have it relatively easy, employing a different technique of igniting their flames, as different as the stings of wasps are from bees. For wyverns, breathing fire changes you. Each fiery breath consumed a firestone from our crops, just as our flames consumed wood, or flesh.

You started your life, it always seemed, with plenty of stones, flaming at the drop of a hat when you were young and foolish, when you were at your most vulnerable. But wyvern lives are long, if you escape infancy. By the time I’d reached what most wyvern would consider young-middle ages, I was rationing my remaining firestones, eating my food raw, and flaming only when necessary. Each time you breathed fire, each time you lost a stone, you also lost the vibrant hue it imparted, the reds, greens, and purples with which we were streaked. Each flame leached colour until you had only one stone left, barely enough to keep your internal engines going. Just one fiery breath from extinction.

Wyverns do not, as a rule, die of old age. Once we pass through the perils of our youth — other siblings, whether the same age or, like Altran, two centuries older, the odd accident (dragon iron can make more than chains and shackles, though there are also natural hazards, like cavern roof collapses…), and the hazards of courtship flights, themselves a great consumer of firestones — there was relatively little that could harm us. Even dragons gave us a wide berth.

Instead, we die a little with each exhaled inferno, each proof of our awesome power. For wyverns, fire is a defence mechanism. Which is why we do not, on the whole, make very good weapons.

I had not known Altran was on her last breath. When I’d seen her, sixty years earlier, she’d been no rainbow, sure, but the edges of her scales had still glimmered with colour. This explained why she was skulking far from prying eyes.

“You’re perfect!” I exclaimed, covering my gasp. “I was going to suggest chalk, or some other sort of make up, but no, sister, you are absolutely perfect!”

“I am nothing,” she spat. “Waiting for such prey as falls into my lair. I’m washed up, no weapon, and certainly not one to strike fear into anyone’s heart.”

So I told her my plan. Slowly, with much shaking of her mighty head and many a weary grunt, I won her around.

“It does rather seem, little brother, that it is my life you’re putting on the line?”

It wasn’t easy, this winning her around bit.

“A myth, then. If this is to be my end, Shurni, then at least it will make for a good story.”

“No end, sister.”

“You promise?”

I held her gaze, though that was mighty hard to do. “If I could, I would. But…”

“Hah! Promise bound and shackled by dragon iron… a sorry state. It might be worth climbing out of this hole, just to watch you try and dig yourself out of yours.”

With that, I think, I knew I had her.

“With your help, Altran. If you do as I’ve suggested — with your own particular flair, of course! — If you remain aloof, and haughty, and imperious… Do you think you can do that?”

She thought long and hard. It was so gloomy down there, in Altran’s lair, that I had time enough for visions. Strange, unsettling visions. Skies criss-crossed by shiny, winged creatures whose wings never flapped. Metal-skinned monsters that flew higher than a wyvern has ever flown and left no room for us, or for dragons, or for griffins. Soulless, lifeless things built by man. Portentous omens indeed, though from the fuzzy nature I could tell it was a far distant vision of a far distant future. My concerns were very much with the present, with the here and now. I still wasn’t certain which way Altran would go.

The cavern rumbled and groaned with her laughter. “Alright, little brother. Let us go and visit this King of yours. I grow tired of mutton. If there is venison and aged beef enough for a decent meal, at least I will not die empty stomached.”

“Grand, grand!” I was delighted, for both of us. “Though before we feast, we will need to make a small detour?”

“Ah yes, that part of the plan. Risky.”

“To which end, any idea of where we should detour to?”

Altran considered, then nodded. “I think I know the place. Though… best let me do the talking, yes?”

* * *

A sight it must have been, two wyverns flying south, one as pale as the clouds, the other darker, as though its shadow. Except in mating dances, neither wyverns nor dragons tend to fly together. And though Altran hadn’t exactly been gorging herself of late, she was still four centuries old and even I was awed by her size. Big sister, indeed.

I circled the King’s castle, flashing the manacles at my ankles to show that it was me, and swooping towards the elevated courtyard in front of the keep in a clear message: clear this space, or be landed on!

Before the stir of guards and onlookers even had a chance to re-arrange themselves, Altran soared in and settled on the roof of the keep itself, skittering down slates and loose stones from the parapet, and extended her wings to look utterly regal and badass and not unlike the heraldic figure she would some day, quite soon, become.

One advantage of me being down below, and Altran being up there, other than her looking like an absolute queen, was that it was obvious that I was the one who would be doing the talking.

“King Ulfred.” I lowered my head. Not a lot, a half-bow, a mark of mutual respect that wasn’t reciprocated. I ignored the consternation of the gathered courtiers, servants, and guards, who, I guessed, hadn’t got the memo that the King had enlisted a wyvern.

“You returned,” King Ulfred said, with a glance to check his elite guard was between me and him.

“Of course. And with an ash wyvern, as promised.”

“Yes, well…” He peered up to the lofty heights of the keep.

“…to whom I promised a half dozen cows.”

“Did you now?”

“Yes. Hungry work, being the most dangerous weapon in existence. But not to worry–they don’t have to be productive cows.”

Ulfred tutted, but fluttered a hand towards one of his flunkies, an implicit see to it.

“So,” I asked, all casual. “When do we go to war?”

He stared for a moment, as if able to see through the walls of his castle and towards his not-so-distant enemy.

“Tomorrow.”

“That soon?”

“No time to waste. My army is ready, and, for now, I have the element of surprise. And you, wyvern, will be by my side on the glorious day.”

I may have groaned. I should have expected this. “I have done as you asked–”

“You brought me an ash wyvern, yes. And I am a man of my word. But my word was that you will only be freed once victory is mine. And it is not mine yet.”

There was hope for him, advisors or not, though it’d be better if he seriously toned down the smug. He also wrongly assumed I was bound to protect him. But my promise had been that my actions wouldn’t cause him harm, it didn’t say I had to put my body between him and arrows and the like. Not as long as I choose to interpret it that way.

“You know, I think you should own the moment,” I whispered. Naturally, everyone within the grounds of the castle heard me. “It being the eve of war and all.”

“How so?”

“Here you are, with two wyverns not ripping you and your army apart. Given our arrival probably sent a few of your less brave conscripts scurrying for the nearest ditch, a display of your mastery is called for, to settle nerves. You should tell your men what you intend, in battle tomorrow. It would do wonders for morale.”

“Well, yes.” He looked surprised. Unasked for, helpful advice. “That does make sense…”

“And don’t forget the cattle.”

He scowled. “Just see to it that your ash wyvern stays on the roof. And extends his wings again?”

Her, I could have corrected him. But I didn’t want to spoil the entertainment.

“Gather my commanders and have the army prepare for my orders. Promise them a cask of ale or two. That’ll still their impatience.” Off the King and his flunkies stalked to advise his generals and to dress in over-polished armour, before addressing his troops. Meanwhile, I caught the distinctive whiff of very nervous cattle. They were scrawny things, I should have asked for two more, and they were doing their best to escape the men dragging their unwilling carcasses into the upper courtyard.

“Where should we…?” a man said, arms bulging as he pulled at the rope. There was something familiar about him… Ah! Our man-at-arms from the cavern had managed to find his way out. Good for him. Now demoted to wrangling supper for wyverns, but that was a better fate than I would have predicted for him.

“Oh, leave them here and close the gates behind you,” I said, gesturing to the roof where Altran waited. “I’ll take them up.”

I probably shouldn’t play with my food, but a wyvern likes to hunt. I caught them, one by one, and carried them to the roof, still struggling in my claws. That way, no-one could see how many Altran ate and how many I snaffled. Not that I felt any remorse about taking my due. I’d flown twice the distance she had, even if I was only half the size.

As we ate we listened to the King’s speech, offering our critique, in wyvern-ese of course. We picked at our meal as the King took my possibly not entirely accurate description of an ash wyvern, and exaggerated it further still. A little light spraying of half-crunched bones happened despite our efforts not to laugh.

But the speech had a rousing effect, as the terrified, skyward gaze of conscripted soldiers gave way to a look of awe, and of possible hope.

“That’ll do it, you think?” Altran asked, after I’d made her stand tall and spread her wings as both King and wyvern basked in rapturous applause.

“We’ll see. Tomorrow. There’s half a cow here, if you…?”

“You have it, little brother. It’s been a while since I’ve eaten so much. Though I think I could get used to it again.”

* * *

We marched out at dawn. An immense throng of men, the steady clank of arms and armour, a painfully slow shuffle forward with Altran and I to the sides so that we didn’t accidentally crush half the army. The horse that the king rode, though blinkered, could sense we were there and wasn’t happy about it. It can’t have been a comfortable ride.

We ascended a low rise, beyond which stretched the open plain where tradition dictated battles between these two nations were fought, much to the ire of those who traditionally lived there. King Francisco’s army was arriving just as we were, and above the bristling tips of spears and pennants, there was—

“The enemy! The enemy have an ash wyvern as well!” King Ulfred exclaimed. “I am betrayed!”

“You are fortunate,” I told him. “That you got one when you did, otherwise you would be at a serious disadvantage right now.”

The King frowned, but returned his attention to the battlefield, as the opposing forces closed the gap between them, while the respective Kings and their respective wyverns kept their respectful distances.

And then… nothing seemed to happen.

For quite a while.

The King’s frown alternated with an expression I can only describe as startled.

“Why are their armies not engaging?” he demanded.

“Probably because you have an ash wyvern, your majesty. A wyvern of mass destruction. Or W.M.D., for short.”

“Well… why aren’t my armies engaging, then? Why do our archers not fire?”

“Because they have a WMD, too. And you did so wonderfully describe what one could do, in your rousing speech yesterday.”

He groaned. “So they’re both just sitting there?”

“I guess.”

“Make them fight!”

“That would be unwise.”

“Why, for hell’s sake?! That’s what they’re here to do.”

Evidentially, his stalemated-pawns had reached the necessary conclusion faster than the King. Perhaps if he’d been a little closer to the sharp edge of the action? I explained, for his benefit.

“If it looks like you’re winning, then the enemy will lose nothing by unleashing their wyvern. And if it looks like they are winning, then you might do the same. A king, at the point of losing his kingdom, does not make entirely rational decisions. As soon as one side unleashes their wyvern, so will the other. Both kingdoms laid to waste. Mutually assured destruction, your majesty. Neither side can afford to deploy their most fearsome weapon, because to do so would guarantee the enemy would use theirs. I’d say the safest thing to do… Hmm. Is to not engage?”

The king stared at me, aghast. He shook his head. “What about you?”

“Me?” I said.

“I have two wyvern on my side. Doesn’t that give me the advantage?”

I’d almost forgotten this is how it all began, with King Ulfred wanting to use me as his weapon. I shrugged. “Sure, but compared to an ash wyvern, I’m neither here nor there. I’m not immune to an ash wyvern’s breath. Nothing is, not stone, not iron, and certainly not flesh. I change nothing. Nor would an army twice as large. Against a WMD, these are lesser matters. On the apocalyptic scale, two Kingdoms each armed with an ash wyvern are evenly matched, regardless of any other forces involved.”

The king scowled. “So what do we do?”

“Isn’t that obvious?” I peered over the vast battle plain, where two armies stood ready and unwilling to hack and maim and kill. “You should try not fighting.”

“Not fight?”

“Yes. I believe it’s called diplomacy. Whatever your quarrel with King Francisco, have you considered talking it out? A negotiated peace? Of course, since you each have an ash wyvern, you’re on equal footing, so there won’t be a lot of concessions made by either side. You’re probably going to have to forgo and forget a lot of historic insults and aggression. Bygones, yes?”

His face was like thunder. There was a snicking noise as Altran restrained her mirth.

“But think on the bright side!” I offered, loudly, to cover them. “Consider the advantages of a strategic partnership, bound perhaps by a royal wedding? Just think; two mighty kingdoms, working together, each armed by the ultimate weapon. Who could stand against you?”

“No-one,” he said, rather sourly. “Unless they had an ash wyvern as well.”

I did my best to act surprised. “They are rare beasts, King Ulfred. They are not given out free with breakfast cereals.” Another allusion that would not make sense until a very long time from now.

He groaned. “I’m worse off than before I captured you!”

“I don’t see how,” I said. “Though of course, if you really think so, I could send your ash wyvern away, tell them you don’t need one any more.”

“But then my enemy would have one, and I wouldn’t!”

“Ah… True. Best look after yours then, hey?”

“What do you mean?”

“Your ash wyvern isn’t a captive, like I am, your majesty. You have no chains or shackles on it — and before you get any ideas, don’t even try, unless you want her flames turned on you and your kingdom. She’s here because she chooses to be, yes? Best treat her well, encourage her to stay. Look after her, feed her, and respect her. Don’t worry, maintaining an ash wyvern is far cheaper than sustaining a standing army. And in good news, nobody died today! I count that as a victory, yes?”

I held out my shackles, to be unlocked.

* * *

Back on the roof of the castle keep, as the army celebrated the — um, draw? Not dying? — feasting on cooked cuts of what we ate whole and raw, (though it would be cooked, before it hit our second stomachs), Altran turned lazily to me, picking between her teeth with a discarded halberd.

“You know Shurni, the whole mutual assured thing doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.”

I grinned. “I am aware.”

“Did you do all of this just for the pun? Wyverns of mass destruction?”

My grin grew wider. That was the problem with anachronisms. You either had to have another wyvern or dragon as an audience, or wait a few centuries for the pun to land. Since humans didn’t live anything like that long, most of our best jokes were mistaken for particularly obscure oracular prophecies. Ho hum.

“Not entirely…”

“Never mind the hyperbole, the blatant exaggeration; able to destroy an entire kingdom, indeed! What does anyone think they could actually do, to convince me to expel my last breath, knowing it spells my certain doom?”

“Quite.” I yawned. It had been a long day. Plus, I’m always sleepy after a good meal, and the King’s men had been even more generous than the King.

“Let alone convince me to use that breath in a specific, towards-the-enemy direction? One wonders why anyone fell for any of it.”

“Because it’s better than the alternative?” I suggested.

“But how long can it last?”

“Stalemates have a tendency to persist, until something radically changes the playing field. As long as both you and—?”

“Bartok.”

“As long as you and Bartok play your parts, I can’t see any reason why we can’t spin this out at least for a generation — of Kings, that is. Ulfred and Francisco are both relatively young.”

Altran drummed her claws on the masonry, leaving deep grooves. “Twenty, thirty years, perhaps? And during that time… do you condemn me to a senescence of silence?”

“Only with humans,” I protested. “You’re not missing much there. I’ll visit as often as I can and there’s nothing stopping you going on the occasional trip. In fact, the worry that you might not come back will do wonders for how attentive they are when you do. I’ve told them what you like to eat and that you enjoy being read to.” I shrugged. “It’s better than spending your remaining days festering in a dank hole, I hope?”

There was silence, as we watched the baleful glow of the setting sun, softened by the smoke of hundreds of campfires around the castle. Tomorrow, most of those soldiers would go back to their villages, to farming and patching up their hovels and whatever else they did when not forced to bear arms.

“Why didn’t King Ulfred remove your manacles?” Altran asked. “I thought I saw the man who carried the keys?”

“You did. But I asked him not to.”

“Why?”

“Altran, how many wyverns are on their last breath, would you say?”

“A few,” she admitted.

“And how many kingdoms are there, on this continent?”

She laughed. “A recruitment mission? With manacles as your calling card? W-M-Ds for all? Well. You’re nothing if not ambitious. Though don’t leave those shackles on for too long, brother, or eat too heartily. They constrict, do bands of dragon iron.”

For the first time I noticed the darker marks on my sister’s ankles. Probably wouldn’t have seen them, if she hadn’t been the colour of ash. The moment hung heavy.

“You know, you may not be doing us a favour, in the long run,” Altran said.

“Oh?”

“This… cold war between humans. It is not quite the same as peace. I know you mean well, Shurni, but it is all under false pretences. It might stop the bloodshed for a while, might give us ash wyverns a temporary home and respite in our old age, but less bloodshed does inevitably mean more humans.”

“Yes… I suppose.” The thought hadn’t struck me.

“Ones who will undoubtedly seek other outlets for their irrational hostility.”

“You think I should make their wars hot, again?” I asked.

Altran sighed. “It probably doesn’t matter in the long run. Our time is nearing an end, little brother. Surely you’ve had the visions?”

I was silent again, for a while. “What happens to us, sis?”

“Who knows? Nothing good, perhaps. If we went elsewhere, you might think our visions would be from there, instead of a dragonless land. Perhaps there is no elsewhere. Or perhaps our visions do not pierce that veil. But that is for the future. Today, at least, we are safe, and I am well fed!”

Altran beat her mighty wings, and lifted into the air, circling King Ulfred’s castle, warning anyone watching from beyond the walls that an ash wyvern was in attendance, (and taking the opportunity to void her bowels over the moat at the same time). Then she settled in the upper courtyard, to listen to bards tell tales of heroes and gods and monsters, accompanied by lilting harp music, while the spot between her ears was scratched by a halbard wielding, very grateful and still somewhat bruised former man-at-arms.

* * *

About the Author

About the Author

Liam Hogan is an award-winning short story writer, with stories in Best of British Science Fiction and in Best of British Fantasy (NewCon Press). He volunteers at the creative writing charities Ministry of Stories, and Spark Young Writers. Sci-Fi collection: A Short History of the Future (Northodox Press). Fantasy: Happy Ending Not Guaranteed (Arachne Press). More details at http://happyendingnotguaranteed.blogspot.co.uk

Unmaking Extinction

by Liz Levin

“I barely catch the American toad, common garter snake, and snapping turtle that fall from my lips.”

“I barely catch the American toad, common garter snake, and snapping turtle that fall from my lips.”

I get the alert about Corinne’s death while Terrible and I are fighting about words. Namely, which ones I should say next time I’m around other humans. He’s lying in the river beside the cottage. Each time he speaks, he heaves his head out of the water. When he’s done, he lets his 300-pound noggin crash below the surface, splashing everything. I’m standing on the muddy riverbank, soaked.

He’s named for terrible crocodile, the English translation of Deinosuchus, his most likely genus. Generally, I don’t speak reptiles or amphibians into existence that died out before we humans spoke English (or existed). Terrible is an exception. He’s demanding I read Chaucer around humans. I remind him I’ve barely begun reciting the Oxford English Dictionary’s nearly 50,000 obsolete words. At a rate of two dozen a day, I’ll finish in five years.

Terrible isn’t convinced.

“But I was alive during the Cretaceous! You think my mate hides in a list of barely dead words?”

“Why not?” I ask. “A common word created you.” He drops beneath the water, soaking me to my neck. “Merde. Keep your head above water while we’re talking. You’re over 30 feet long. You’ll empty the river.” Terrible was designed to eat dinosaurs, and it shows.

“Common word,” grumbles Terrible. “There’s nothing common about me.”

I couldn’t agree more, but we both know I wasn’t capable of linguistic feats on my curse day, five years ago this Saturday. Terrible was born on that day, before I found the cottage and before I started recording what I say within earshot of humans so I can replay it to determine which species belongs to each word. I’ve tried to recreate those first impassioned sentences I said in front of Mama and Corinne, but as much as I try, I’ve never birthed another Deinosuchus. And though I’ve uttered the curse that made Serpent, that word has never birthed another.

You may wonder why I say birth or born. After all, lizards and amphibians drop from my lips when I speak English within earshot of humans, not from my womb (thankfully). I ask you, are there better words? I’ve tried vomit. None of the creatures born speaking like that.

“Is he still complaining, Vivienne?” asks Serpent, gliding across the mud to coil up my leg and around my waist, like an ornate belt. He’s pretty enough to seduce Eve. His skin bears a geometric pattern of emerald, sapphire, and gold. “Living gems,” he likes to say, “much better than your sister’s dead rocks and flowers.” He’s not wrong. “You haven’t made a girl for me, and you don’t hear me complaining.”

“Another of you?” I cross my arms and shiver, even though it’s 86 and humid. “Terrifying. Last thing we need is you reproducing.”

“Impossible to improve perfection,” Serpent says. “Too true. But I came to tell you your light-up machine interrupted my sunbath.”

I glance at my phone on the picnic table, a safe distance from the river. Electronics and brackish water don’t mix.

“I’m working on it, Terrible.” He’s moved his head below water again. I talk to his bulbous eyes. “I know you’re lonely.” I am too. I don’t say it aloud. I don’t want to offend anyone.

“Putain de merde.” Corinne Barreau, Wife of Phoenix’s Golf Course King, Dies at 22.

The service is Saturday, on the fifth anniversary of our curse.

* * *

I ride my mountain bike along deer trails until I reach the Phoenix exit. Turning back toward the woods, I see an electrified fence topped by razor wire. Signs caution: Toxic dumping site. Stay out. Behind the fence lies desert. If I turned back with the intent of entering, I would find an unlocked door. Behind it is a primeval forest with sequoia-sized trees.

That’s the ecosystem outside Phoenix, but the woods are a patchwork of habitats, from deciduous forests to tundra, from peat bogs to estuaries, like the one by our cottage. I’ve wondered whether our cottage is beside an estuary because it’s where women with our curse always live (if we survive) or did the cottage move to the biome Terrible would need?

I’ll leave it to you to answer that question.

I like to think that this wild place contains all the famous cottages, even Baba Yaga’s chicken leg house. So far, I’ve found it disappointingly empty of humans and witches.

And fairies, thankfully.

Serpent is cozy in the granny basket as I ride six miles to the Golf Course King’s estate, a.k.a. Hugo Von Brandt, my ex-fiancé. It’s dawn and Phoenix is unbearable. I arrive early to wash up in the pool house. Unscrewing the pineapple-shaped finial from the iron railing beside the door, I retrieve the key. I change from dusty cutoffs to the requisite black dress, and an opaque black veil looped to catch anything that drops from my mouth. I don’t plan on speaking English. Mama spoke French in our home. I’m fluent enough to pass as a native, a ruse I’ve played before, but it’s dangerous here. After all, Mama thinks I’m dead.

I shoulder my backpack, leaving it open at the top and cautioning Serpent not to stick his head out. He’s a curious snake.

The service is in the greenhouse. My veil sticks to my face in the humidity. My sister is the only one here, lying in a sapphire-colored casket beside the podium. I walk down the center aisle, past empty chairs. Before I revealed Mama’s lies and poisoned our engagement, Hugo and I were to be married here.

Oh, Corinne. In death, she looks like porcelain. Fragile. Like someone who would shatter under an ambition like Mama’s.

As the favored child, I had years to build defenses against Mama’s avarice disguised as affection. People say I looked like Mama from birth, and so, like a good little narcissist, she loved me at first sight. Corinne, my junior by a year, looked like the lover who left her. Accordingly, Mama handed her a broom when she was in kindergarten.

Classmates thought it better to be me than her, even though they adored Corinne. They saw Mama lavish me with unmerited praise; they saw the patches on Corinne’s hand-me-downs. They were right enough. I helped when Mama wasn’t watching, but after Mama caught me chopping fennel for Mama’s favorite bouillabaisse — my recipe perfected over years — she punished Corinne.

Mama ordered her to draw water from the new wishing well that had appeared the day after the mayor admonished the media for implying Phoenix was running out of water. Corinne returned and Mama emptied the pitcher on the cacti while scolding her youngest. Corinne’s apology yielded a tiger lily, uncut emerald, and thorned rose that dripped blood. Mama sent me to the now blessed well.

“You can still save this engagement, mon bijou. If your pathetic sister can win a blessing, so can you.” I suggested she go in my stead. She rubbed her neck, swallowed, and gestured toward the door. Oh Mama, I understood you well. Even then. You knew the price.

When a fairy disguised as a princess requested water, she looked as though she stood behind a screen of bloody thorns. I refused and she cursed me. Or so the story goes. The well disappeared. Mama said we needed to talk, drove me to an empty patch of desert, and left me. If I hadn’t uttered that curse after she left, birthing Serpent who led me to our cottage, I would have died. Even with his help, I nearly did.

Someone moves beside me and the casket. Trim in a custom suit, blond hair freshly cut, skin leathered from the links: the Golf Course King of Phoenix, Hugo Von Brandt, the golden chariot to wealth Mama raised me to catch.

Hugo doesn’t recognize me in my veil. “Gorgeous, isn’t she?” He nods to Corinne’s heart-shaped face and soft brown hair. “You knew her? We all miss her more than words can express. She had so much left to offer.”

I choke back a curse before it becomes a word. It sounds like a sob. To offer? Like diamonds for the price of a word? How would Hugo pay to water his expanding empire now? I bow my head before I walk away. He doesn’t comment on my silence.

During the ceremony, I lean against a shadowed pillar and listen to Spanish-speaking servants praise the late Mrs. Von Brandt who always spoke to them in their language. The chef tells a humorous story about her notorious hatred for smart phones, and how she tricked him into giving his phone to her for the day to help him overcome his addiction. I straighten at that. What were you planning, Corinne? Hugo or Mama manufactured her hatred of phones, for certain. If her curse worked as mine does, she could type English words without activating her blessing. My movement wakes Serpent. He drapes himself across my shoulders, hidden by the veil, whispering questions in my ear while I shush him.

The group in front of me gossips through the last speeches.

“Did you hear how she went?”

“Choked.”

“My ex performed the Heimlich on a guy at a steakhouse.”

“She wasn’t eating when she died.”

“They say they found her—”

I squeeze through the crowds until I’m in the main house, on my way to the room Hugo said would belong to me after we wed. Serpent and I search for anything that will tell the story of Corinne’s death, or life. He slithers under and behind while I scrutinize photographs of carnivorous flowers hanging from clothespins. She had an artist’s eye, even if photography was never her specialty.

After moving a three-shelf bookcase, at Serpent’s suggestion, I find a safe built into the wall. Or magicked there; it resembles the one in my cottage. Just like mine, I find no obvious lock. There is an iron sculpture of a carnivorous pitcher plant. “Do you think it works like mine?”

“Only one way to tell.”

With trepidation, I lift a finger to the bulbous flower, preparing to plunge it into the dark opening. My safe features a cobra’s open mouth. I survived my first attempt to open that safe. Unlike this one, it was designed for someone with my cursed blessing. “Wish me luck!”

“You already have me.”

I’m not surprised when the flower’s cylinder constricts around my finger. I feel a sharp jab before the pressure releases and the door pops opened. My finger numbs, then my hand. Already it’s spread more than my safe’s toxin does. I’m immune to reptiles’ and amphibians’ toxins and venom. Here’s hoping flower toxins are similar enough. Only my immunity is magical, not biological, and there’s no promise I’d be protected even if the safes’ toxins were chemical twins. The numbness creeps above my wrist before I panic.

“Serpent, help!” I whimper. He strikes, biting the inside of my elbow, right above the line of numbness. The sharp pain of Serpent’s venom chases back the numbing effect of the safe’s toxin. It’s like the blasting away of cobwebs, followed by the clarity of knowledge.

After wiggling my fingers to shake away the pain, I open the door to the small safe and slide her journals into my backpack. I hesitate before adding the pouches of gemstones. I’ll make better use of them than Hugo or Mama would. In the attached bathroom, I wash my face and change back. I wrap a floral scarf over my hair and around my face to hide my identity (it’s too lightweight to support births) and leave this gilded cage.

* * *

I’m pushing up my kickstand, congratulating myself on my smooth exit, when Mama finds me. “Vivienne! I thought that was you, my sweetest daughter!” she cries in French. She’s wearing white, elbow-length gloves with shiny black buttons and a black sundress with a scattering of white roses trailing down the belled skirt. Her chestnut hair is gathered in a soft roll. She looks chic, just as I remember her. “I thought I’d lost you, but here you are, like a miracle on the day of my greatest sadness.” I don’t respond as she smooths away my veil and kisses my cheeks. She misunderstands my silence. “Oh, sweetest girl, you can speak to me in French. Your… gift. It only happens when you speak English. Use our mother tongue and you will have no worries.”

Gift? I wonder, tensing. Why does she think I have a gift? She was first to call it a curse. It is never good when Mama changes her mind. I sit forward on my bike. She stands in front of the wheel, grasping the handlebars. Trapping me in her false affection. I shift forward slightly, testing her hold. She gives a nervous laugh and takes a step back on her red-bottomed heels. “Careful, sweetest! You only have one Mama. Best not to run her over.”

I shrug. “You didn’t lose me, Mama,” I finally respond, in French. “You kicked me out. I almost died.”

She tilts her head and smiles. “But you aren’t dead. You left the car when I was distraught, incoherent, unable to give chase, and you survived. You thrived. You are still so beautiful, my sweetest Vivienne, even like this.” She caresses my head, masking her sneer. My hair is long, like hers, but the chestnut waves are dull and snarled. I ran out of conditioner last month and haven’t gotten a chance to buy more. I’ve been selling rare breeds of reptiles and amphibians to the San Diego Zoo. I like their conservation programs and my contact. We speak in Spanish, his first language. He believes that French is mine. Sometimes he tries to teach me a few English words. I decline. His hair is black, shoulder-length, glossy. I’m sure he uses conditioner.

“I need to go, Mama.” I turn the wheel and rock forward on my bike. Just a bit more and I’ll be able to roll by her. We’re far from the parking lot and I know this area. I’ll lose her, easily.

“No, don’t you leave.” She’s replaced sugar with steel. This is her Corinne tone. Is it any wonder my younger sister acquiesced when Mama finally coated her words with sweetness and acted as though she’d always loved her? But that won’t be me. “I figured out your sister’s gift,” she says, drawing a gold notebook from her clutch. She opens it, revealing a handwritten lexicon so like the one I left in the cottage, it makes my eyes smart. These moments are the most devastating. When Mama does something that demonstrates that she was right. We are the same. Even our handwriting is almost identical. “See, at first the gift seems random. You speak, and out fall hideous toads and frogs, of no value to anyone. But all we need to do is what I did with your sister. We just need to find the words that make the valuable things, like alligators that can make beautiful bags. She caresses her clutch. The pattern is subtle, just like the smooth skin of an alligator’s belly.

“Can I see?” I ask, reaching for the notebook. She steps to the side to hand it to me and I’m off, wheels spinning over the pavement, past split-levels with hardscaped yards and alleys until I’m out of the city and on my way home.

* * *

I stop a few times to hydrate and make frogs outside gas stations. I duck my chin into my open backpack, pretending to search for something. I speak the words as customers enter and leave convenience stores, just loudly enough to register without inviting a response. I know the words that create males and females of all six species of leopard frog endangered in Arizona. I choose a species and make two dozen males and two dozen females. Serpent grumbles from his spot beneath the frogs.

I stop at a sheltered spot on the way to the Phoenix entrance and acquaint them with their new habitat. None of them talk to me. It isn’t surprising. I’ve created a lot of leopard frogs over the years. Mostly, they only speak when they are the first of their species.

“Home?” asks Serpent. I nod. “Finally.” He falls back to sleep on top of my funeral veil and dress.

I study Corinne’s journals before bed. Most are pre-curse, filled with charcoal drawings of high school friends drawn with scales and tails, fawning over a sad doe wearing Corinne’s face. They offer her small things — pencils and dandelions — while gossiping about her helplessness. Small breasts, small bones, small dreams. Mama is absent. When I appear, I am human and alone, clenched jaw and furrowed brow. If she saw me now, I’d look the same.

I open the last journal. The top two-thirds of each page is filled with colorful scenes of monstrous people, interspersed with words, each composed of a particular flower or gem. The words drip in blood that dries beneath the too-bright sun. The bottom third of each page depicts charcoal caves beneath the earth’s surface where humans lie on hammocks, dreaming.

This is Corinne’s lexicon, I realize. Not the tidy gold journal filled with Mama’s even loops.

* * *

Sharp knocking wakes me the next morning. I’m lying on my side, a wedge pillow at my back and a body pillow between my legs to keep me in position. Serpent lies coiled beside my face, ready to bite me if I roll over onto my back. These are just precautions. Even if I talk in my sleep, my words shouldn’t matter because I’m the only human around.

“That we’ve seen,” Serpent would caution. If I believed his horror stories, I’d think there are hordes of humans outside this cottage, with their ears pressed to the thin walls, just waiting for me to mumble something in my sleep.

The knocking. There are people and I’m not dreaming. I rub my face and crawl over pillows, tripping my way to the bathroom. It’s small, with a corner shower and a pedestal sink, but it’s plenty of space for me. I wash my face and gather my knotted hair into a bun. I’m wearing sleep shorts and a camisole, but anyone who is at my door at the tender hour of… noon… can deal with it. This is my first visitor so it’s on me to set low expectations.

I walk through the family room, past an overstuffed sofa, and gecko-print-covered recliners. (No, I didn’t buy it. The cottage knew I was coming, just as it will know when you’re on your way.) The artwork changes each time I sleep. Today, a black and white photo of Terrible spans the sofa’s width. His mouth is open, showcasing his teeth. I open the door, and Mama drops the bronze salamander-shaped knocker. She’s incongruous in her pleated black slacks and cream blouse. Behind her, an Escalade sits on a freshly paved driveway that connects to a road. Last night, there was a dirt trail barely wide enough for my bike’s tires. My gaze skitters between the new features. Finally, I say, “There’s a road?” I barely catch the American toad, common garter snake, and snapping turtle that fall from my lips.

“In French,” Mama reminds me, shouldering past me into the cramped family room. “Really, sweetest, did you just wake up? You’ve wasted half the day.” She sets her alligator-skin purse on the coffee table, shifting aside my dogeared copy of Amphibians of North America, and directs a blinding smile my way. “Are you ready to get to work? I’ve made a list of all the best ones.”

Maybe she’ll leave if I ignore her. I walk into the dining room and open three of the empty terrariums sitting on the long table. I place an animal in each, add water and dried food, and return to the family room.

Mama is still there, now holding a green notebook. Her smile is gone. “Is this any way to treat your mama? You offer food to those pests before you offer me a glass of wine? What happened to the manners I taught you, Vivienne?”

“I don’t have wine,” I say in French.

“No matter,” she says, gesturing as though to wipe away the last ten minutes. “As I was saying, I know how to make us rich.”

“Aren’t you already rich?” I ask. “Don’t tell me you didn’t profit off Corinne’s gift.”

Mama glances away, widens her eyes at Terrible’s photo, before meeting my gaze. She takes a deep, yoga breath, exhales, and sits on the edge of the couch with her back to the photo. Hoop earrings shimmer like pearls. Nacre, or mother-of-pearl, the luminescent secretion mollusks use to coat errant grains of sand. Pearls are rare. Mother-of-pearl coats the inside of every mollusk shell. The earrings are cheap, considering.

She sighs, rests her face in her hands, rubs it gently. When she looks up, lipstick, liner, foundation, and powder are unmarred. “I made a mistake, mon ange. I went straight to your ex-fiancé and shared the news of Corinne’s gift. He married her, of course. He was no fool. After that day, he never left me alone with Corinne. Not until he left town for business. And then we barely got started before…”

She pauses, shakes her head as though to redirect her thoughts.

“But with you, I’ve learned. You were always the better daughter, sweet Vivienne. I’m so sorry I didn’t see your potential at once.” She opens the green notebook. There, in slender loops like mine, she has written a plan to monetize my curse, because if I used it the way she suggests, it would curse all who breathed life through my words. “Some of them aren’t pests, see? Some have purpose.”

I take the book, her earrings swaying as I pull it from her grasp. I glance away before she notices my tears. In French, I say, “Mama, why don’t you get yourself a glass of water while I read.”

I open the door, muttering “mother-fucking nacre” before I’m out of earshot. I catch a warty toad for the compound adjective and an unknown crocodilian. I set them on the picnic table, rubbing my finger across the crocodilian’s back. I’d forgotten nacre was identical in English and French. I’d research its species later. On the muddy banks of the river, I draw my knees to my chest and wait.

It isn’t long before Serpent joins me. “You heard?” I ask.

“I was under the couch. Slid out the snake door when your mother was in the kitchen.”

Terrible splashes up from the river, hoisting his front legs onto muddy land. I glance at my drenched sleep shorts and camisole, thankful I’d chosen black. The sun is at its zenith, drying the beads of water off my arm. I rest my head on my knees. “I don’t know what to do about her,” I say.

No one speaks. Terrible wasn’t there to hear Mama, but he knows the stories. They both do. Five years together. Worth more than my twenty with Mama.

“Did you hear what she said about Corinne?” Serpent finally says.

“What did that witch say?” Terrible asks. I’m surprised. He likes the witches in the stories I read to them. He says they have the best parts.

Serpent’s voice shifts to a high-pitched whine that sounds nothing like Mama. “’After that day, he never left me alone with Corinne. Not until he left town for business. And then we barely got started before…’” It takes me a moment to ignore the voice and process the words.

“You think…”

“I do.”

“What do you think?” I ask. I don’t even know what I think.

“That the witch killed your sister,” Terrible says. “That’s how it always goes.”

“I don’t know,” I say.

“Ask her,” Serpent says.

“And then?” I ask.

* * *

I move the picnic table closer to the water. I set the green notebook on top. Terrible’s bulbous eyes watch me. Serpent slithers across my shoulders, silent. I say, “Our plan is horrible.” I touch the green notebook, thinking of Mama, the crimes she’s proposed, and the one she may already have committed. “Maybe she didn’t do it.”

I return to the cottage to gather Mama. “Let’s sit in the sun to talk.”

She follows, grimacing at the muddy ground and weathered bench. She sits and disturbs the air with talk of alligator hides and import laws. “But don’t fret. I’ll handle logistics. You study your gift. Do you know which words link to each species? So often it’s nonsensical. You know what Corinne said for opal?” She whispers a crude word. I laugh, surprising us both.

“Mama, what happened to Corinne when Hugo left? I know something happened.” I pause, rest my hand on top of hers. “I won’t blame you.”

Her eyes glisten. She cried in just this way — a few tears that didn’t smudge her eyeliner — when she drove me to the desert five years ago. “Oh, Vivienne, mon bijou, it was tragic. We finally had time alone, our first since the wedding, and your sister refused to help. She just wanted to talk. In French! I gave her wine and a few pills, just to relax. She was so tense! I tucked her into bed like when you were girls.” She never did that. For either of us. “Left for a moment — to grab a glass of merlot and our notebook — and when I returned, she was still.”

“Why, Mama? Why was she still?”

“Her mouth, her throat.” She looked up at me and her face was wet, eyes smudged. “Filled with pearls.” She looked around, probably wishing for her purse and its tissues, before she rubbed her hands across her face and dried them on her pleated black slacks. “But that’s all in the past. Now I, we, can start over.”

“You’re right,” I say. “Stay here a moment, Mama. I’ll get your tissues for you.” I look to Terrible as I leave, all but his eyes beneath the water, invisible if you don’t know where to look.

I wrap myself in a robe before sitting on the gecko-patterned recliner. Even after an hour in the sun, my clothes are damp. I lean back and study Terrible’s photo. After the third sniff, I open Mama’s clutch and dig out the package of tissues.

I think about pearls. A common grain of sand inspires its creation; common words produce them. Before Mama left me in the desert, she punished Corinne for my curse. “You ruined your sister,” she said, as she held the painting Corinne had gifted her on Mothers’ Day over the kitchen sink and set it on fire. Corinne cried, “Mama, stop, mama, stop, mama, stop,” and black and white pearls bounced across the floor.

When I left my childhood house, I still believed Corinne was gifted. She’d leave, I thought, Mama would have nothing, and Corinne would have everything.

I almost died in the desert. Serpent saved me, led me to the cottage. Years later, when I made it out of the woods, I learned of her marriage. Hugo is an ass, I thought. But at least she’s away from Mama.

I should have known how much a person will do for a bit of sweetness, after a lifetime without. Delirious from a mix of alcohol and sedatives, Corinne pleaded with the woman who cried only crocodile tears. And she died, choking on pearls.

* * *

I shower and change into clean clothes before I go outside. Mama is gone. A hybrid pickup sits in the Escalade’s place on a drive that now curves toward the San Diego entrance. I lift the cover on the truck bed to find it filled with premium habitats. I sigh, not happy, exactly, but relieved that the cottage agrees with my choice.

Terrible lies beside the river, bulbous eyes closed. His back looks like a mountain range, burnished copper in the sun. Like Serpent, he is a living treasure. “Well?” I ask because I probably should.

He grunts.

“Indigestion,” Serpent says. The unknown crocodilian lies beside Serpent, sunbathing.

“Do you know the species?” I ask because I’ve given up predicting what Serpent knows.

“She hasn’t said.”

Terrible raises his head from the water and lets out a nauseating belch. I pinch my nose until the odor clears. I wipe the tears from my eyes and rest my palm on the ground beside the baby crocodilian. “You speak?” I stroke her baby-soft skin. Someday the nubs on her back will be craggy mountain ranges. Today, they look like strings of burnished pearls.

“I’m not mother-fucking nacre,” she snorts. “I’m mother-fucking Necrosis. Pleased to meet you. And especially you,” she says, turning her snout toward Terrible.

My laugh, when it comes, is more than a little hysterical. “Cell death? Terrible, her name means cell death.”

“She’s perfect,” he says, gently resting his snout on the riverbank so that the mate who just traversed my narrow esophagus can touch her nose to his.

I leave them to it. Inside, I gather Corinne’s journals and add them to our safe. They join the lexicons and diaries written by the women who have made it to our cottage. (There are gaps. Sometimes we do burn in the desert or freeze in the woods.) They belonged to ages when everyone witnessed the power of magic, or prayer, or science. None witnessed the power of dinosaurs. Perhaps you will.

* * *

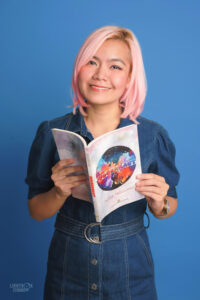

About the Author

About the Author

Liz Levin lives near Chicago with one vociferous cat and the three other humans who cater to his needs. An alum of the Stonecoast MFA program and Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Workshop, her work is published or forthcoming at MetaStellar, Flash Fiction Online, and Metaphorosis.

Silver Bones

by Michael Steel

“In another world, a simple rat like me might be the king of the world. Kings don’t need beautiful graves to be remembered.”

“In another world, a simple rat like me might be the king of the world. Kings don’t need beautiful graves to be remembered.”

My ma always said if I was going to die, I ought to get a beautiful grave, with a nice tombstone and everything, so when I was long gone every rat that passed by would know I existed once. Graves, she said, are the only places that little rats like us can affect the world once we’re gone. Not that any of the bigfolk would notice it. They’re too busy with their bigfolk nonsense to even notice us when we’re scurrying underfoot. That’s better for us, though — anytime they do notice us, they stamp us out. But you’d know all about that, wouldn’t you?

Somehow, I don’t think my ma would call this a beautiful grave. A filthy subway tunnel in New York City, with only the rumble of the trains and the chatter of the bigfolk to keep me company. And you, of course. You’re always here, in the murky dark shadows. Watching, lurking, waiting for me.

I think the walls were beige once, but now they’re an awful, filthy gray. It stinks in here. Stinks like rotten banana peels and misery. I don’t want to die surrounded by the smell of misery. And I can’t stand bananas.

I was stupid today. You see that bigfolk over there? Yeah, that one, in the rags. The one who’s stinking the whole place up. He probably hasn’t cleaned himself since before I was born! He always hangs around here, but he never gets on a train like the other bigfolk. He just sits on that bench there, and sometimes he smokes. Today he had a sandwich. A sandwich sent from heaven. The smell was so good, you’d never believe it. I thought I was dreaming at first, but I knew it was real. I watched him for a while as he ate it. Watched him from my hidey-hole. I could feel my stomach screaming for the sandwich. I wanted to scream for it. It had bacon in it, you know. Bacon!

Finally, the dirty bigfolk put the sandwich back down onto the floor. I thought I’d just scurry over and snag a piece of bacon. Nothing big, nothing he’d miss. I got the bacon in my mouth, and oh boy it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever tasted. I couldn’t stop myself, I ate it right then and there. If only I had just run back to my little hole, the bigfolk would have never even noticed me. But he looked back down and saw me. His eyes, they were gray, such a dirty, dark gray. Like the water down in the sewers. They were furious, though, and sewer water never gets furious.

He yelled something at me, and before I could run there was a boot in my stomach that sent me flying and now I’m here, dying under the subway tracks and I’m just so tired, old friend. I’ve seen you so many times over the years, taking my ol’ ma, my brothers. Taking even bigfolk sometimes. And now that I’m the only one left, I guess you’re here for me.

I keep thinking, over and over, no! No, not yet. But it is my time now, isn’t it? Or else you wouldn’t be here. Old buddy. Old pal. You’ve been here as long as I remember, always following me around, floating over my shoulder. Only I never turned around to see you, even when you were everywhere. It’s only been a year. Hardly a year. I only ever saw one winter. Please, I don’t want to go yet. What about my beautiful grave?

I had no say in any of this. Why aren’t I a bigfolk? Why did I have to be a rat, downtrodden and hated by everything? In another world, a simple rat like me might be the king of the world. Kings don’t need beautiful graves to be remembered. But here I search for food in rotten dumpsters, until some bigfolk notices me enough to end my life, without barely caring. How is that fair? They can kill us with a swift kick of a boot or a quick shake of a poison bottle and never think of us again. They end so many lives, every single day — and they don’t even care.

I guess I could appeal to the heavens, the rat gods, and the rulers of the real world, but I know they won’t listen. I’m just a little sewer rat drowning in the filth of the subway tunnels. Why should they care if I live or die?

The only thing left for me to do is run.

I can hear my life leaking out of me when I pant and wheeze. My claws hurt from running on the concrete. I’ve spent my whole life down here, and somehow only now I’m lost. The tunnel is so dark now, rushing by like the fleeting life of an unloved rat. I’m running as fast as I can, but you’ll always catch me. You’re in every shadow, every dark corner.

The tunnel’s getting bigger, I know it is. I’ll never find the exit now. Why are you doing this to me? I don’t want to die.

I don’t want to die alone. I could have been a world champion, if only somebody had cared. When I’m dead, I’ll be nothing more than just another mangled corpse, another dead rat out of thousands of dead rats. My dusty bones will lie in the mud for four centuries, slowly turning to silver in the darkness. And even in my silvery death, I’ll be beautiful, more beautiful than the foolish bigfolk who crushed my ribcage for a bacon sandwich. He will never be as pearly perfect as my cold, dead bones.

I will be my own beautiful grave. I hope my ma’s proud of me now. Maybe one day somebody will find my smooth white skull and they will hang it on their bracelet. Maybe then somebody will remember me.

I’m ready now. Take me home to Ma.

* * *

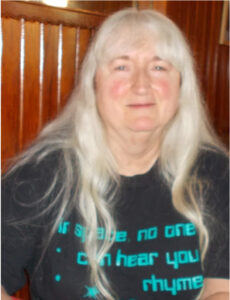

About the Author

About the Author

Michael Steel is a high school student currently living in Vancouver, British Columbia. He lives with his parents, brothers and ridiculously fluffy cat, Taco. His hobbies include fantasising about rats, writing about rats and playing Block Blast.

Queen of the Hungry, Queen of the Few

by Leo Oliveira

“Lions are no easier to fool than anyone else, but they were built to chase lightning wherever it strikes. That’s what thunder does.”

“Lions are no easier to fool than anyone else, but they were built to chase lightning wherever it strikes. That’s what thunder does.”

Before the lions came and ate our mother, she filled our nursling ears with tales of The One Who Races the World.

“Races the World was as quick on her feet as she was in her mind.

“She was a queen among cheetahs. A legend across the savanna.

“Impala frightened their cubs with invocations of her name. Hyenas did not steal her kills, for she was strong as well as fast, and she could drag the carcass of a water buffalo up a tree like a leopard, so that only the boldest of baboons would dare challenge her for it.”

Races the World was like a goddess to me. Countless silver nights curled up together in the long grass sheltering under a fallen acacia, begging our mother to tell us another, and another, and another. Of Races the World’s adventures, I could never get enough. I used to wish my mother had given me a proud name like hers, a bold name like hers, but I am only The One With Tiny Spots.

My brother is The One With A Dancing Tail and my sister is The One Who Sheds Black Tears. We had seen the rains come but once and we were three days and nights alone. Three days and nights as orphans. Several times that spent hungry, near starved. Our mother could not feed us anymore; not while she fed the fly-bitten bellies of lions.

Dancing Tail complained first of his empty stomach and how weary he’d grown of running, so I stopped him in the brush to chase down the fresh scent of a hare.

“I appreciate you,” Dancing Tail said, stretching out his long limbs beneath him. I considered giving him a warning not to grow too comfortable, but we’d not rested since before, and we were all tired and hungry. I didn’t have the heart to push him. Not even if our mother’s stories had taught us to be stronger.

Black Tears said nothing. She was the better hunter of us, what little practice we’d been given. But her eyes — measured, focused, and still — told me not to make a mistake. They said that she would not help me if I did.

* * *

I stalked the hare like our mother had taught us to stalk, patient and slow. “We are cheetahs, and we are not given second chances.” If I did not understand it before, I understood it then.

The hare was young and reeking of milk-scent. I followed her trail between brush stalks and golden swaying grass reeds until I spotted her ears. Somewhere out there was a litter of hare cubs, squirming and blind and useless. Possibly fur-less. All they had was their mother, and they would die quickly without her.

The first impala we ever ate was a young female our mother had brought down at the edge of the plains. She’d taught us between heaving breaths how to pull the skin free, how to split open the belly, how to fill our stomachs with the best parts of a carcass quickly, before hyenas or lions or painted wolves came to steal it.

I had never seen a dead impala before. I did not know the moist-slick mass, still blue with its fetal sack, was an unborn cub until our mother told us. I’d crunched through its soft skull, and I did not feel any guilt. I felt none for the hare now, but I twinged ever-so-slightly imagining her litter, tiny and helpless and so much like me and my siblings — my chest clenched with hurt.

Then I ran.

The One Who Raced First was born from a bolt of lightning that’d lanced down and struck the first of the First Cats. We are bolts from the black. We are energy incarnate. We burst to top speed from standing in three heartbeats flat.

Young and underdeveloped as my bones and muscles were, I closed in on the hare. It had not one hope of outstripping me. The ground became a blur. I stopped moving my legs for it was them that moved me. Inertia and instinct.

“If you think, you fall,” my mother had said to us. But that was why Black Tears caught more prey than I ever did.

A scent hit my nostrils through my next gulp of air, and I could not help myself. I slid to a halt. The hare’s fleeing footsteps faded in my ears, but I was not watching. I did not care.

We were born from lightning; lions came from the thunderclap after.

* * *

“The lions! The lions are here!” My fur trembled, feverish with race-rot — that sinking, heady feeling that follows a sprint to the edge, when the world swims before the eyes and the sun glares inside the skull.

Dancing Tail sprang to his feet. “What, where? Did you see them?”

Black Tears remained sitting. “I thought you left to catch a hare.”

“I called off the hunt because I smelled them. They’re close. I don’t know how close, but we must leave before they find us.”

“You smelled them, but you did not see them, and so you abandoned the hare.”

I have never wanted to kill my sister, but at that moment I came close. Her callousness dug into me like her tongue was tipped with poisoned spines. I hissed and spat in frustrated circles. I held my own tongue, but I held it barely.

“We don’t have to fight each other,” Dancing Tail said. “We’ve tricked them before.”

And indeed, he was right. The lions had not been content with our mother. This was not the first time their scents had drifted down to us on the breeze — they weren’t even hiding, that’s how we knew how little we meant to them — and we made use of the environment every time they came near. Switchbacks through the brush, false trails, looping paths that intersected with one another and shot out in different directions.

These had also been tricks our mother had taught us through the old tales of The One That Moves Shadows. If Races the World was like a goddess to me, Moves Shadows was like a goddess to Black Tears.

Black Tears gaped her jaws wide in a tongue-curling yawn. I forced my twitching tail to lie still.

“Let’s get it over with,” Black Tears said. “Hopefully you didn’t scare all the prey off with your yowling.”

“Only the ones slow enough to be caught by you,” I said.

“All of them, I see.”

I glared at my sister. She gave me a blank glance back. Then she turned away from us.

I sighed and pawed at the parched orange dirt. I wished she didn’t follow so closely to Moves Shadows’ favourite lessons, the ones our mother had so often repeated:

“The strong cheetah she is; she hunts alone.”

* * *

It took us until the first high heat of the day to finish our rounds. By then we had no appetite for hunting. Fear is one of the great constrictors, and we had spent so very long afraid. But we couldn’t risk standing still, either. While cheetahs sleep at night, lions are wide awake. To stop was to die. We needed to take every opportunity we had to make distance.

So, we started off and did not stop until tingling exhaustion forced us to. I sank onto my side, soaking in the cool dry earth. Dancing Tail curled up beside me. I shed heat through my open mouth, and each inhalation raked in great lungfuls of evening scent.

The musky tang of distant zebras and wildebeest skipped across the breeze to me. Dust, pressure, and the coming rains. Beetles and bugs and moisture in the air. My sister, my brother, and—

Lions.

I scrabbled upright, huffing, filtering through the scents for new and old, strong and weak, predator and prey. I had not been mistaken.

The lion scent had not gone away. If anything, it had grown stronger.

“Wake up,” I said, nudging Dancing Tail and Black Tears in the ribs. “The lions are coming.”

I could tell right away that they did not want to believe me. But the chance of ignoring a serious threat for a few fleeting moments of ignorance was not worth the trade, so they parted their jaws and confirmed my findings for truth.

“That’s impossible. How did they find us so fast?” Dancing Tail shivered. He was already the smallest of us, and he seemed to shrink further.

“They learned what we were doing.” Black Tears’ tail tip flicked up as if batting off flies. “That’s what we get for doing the same things over and over again. And whose idea was that?”

“Don’t hiss at him,” I said.

“Then you better hope you have a plan.”

I hesitated. This was not for lack of an idea, but for the nature of the idea I had. But both my littermates were staring at me, waiting, and I lowered my eyes as I said, “There’s always the Wall.”

The Wall was a dangerous place. A deadly place. Our mother had warned us in thrice as many words: humans with loud sticks and dogs, rock beasts on baking black paths, fields upon fields where nothing grows. The whole world changed on the other side of the Wall, but what other choice did we have?

“Maybe the lions won’t follow us past,” I continued. “Nobody crosses the Wall. And we can’t be far from it by now. See the baobab splitting the rocks? It’s the vulture skull stones.”

Our mother had brought us to the edge of that baobab once to tell us it was the edge of her territory. When we’d asked her why she didn’t go further, that’s when she told us about the Wall.

Neither of them liked my plan; I could tell this too. But nor did they see any other option.

“All right,” said Black Tears. “To the Wall.”

* * *

The lions stalked us throughout the night.

Several times we swerved off to the side and attempted to bed down, but the lion scent strengthened in half a cooling cycle or less without fail. They kept on coming. We had no recourse but to forget about sleep. Forget about resting. Move and move and move some more.

Cheetahs were not made for the night. We were born of lightning and nursed by daylight. Divots and grooves appeared beneath our paws, and any misstep into darkness could lead down gulleys or dry streams or crocodile-infested rivers. We had no way of knowing. We’d never been there before, and we could barely see.

At the point when the moon had begun to arch its descent, Dancing Tail took the lead. It was his turn to sweep the earth and guide us through the treacherous landscape. I kept my nose to his tail-tip, ignoring how it made me itch and sneeze. It was about the only way to keep together, our scents mingled and muddied as they were.

Then my brother disappeared.

“Dancing Tail?” I called out as he yelped — a sound that grew dimmer beneath a shatter of small stones down below.

Black Tears crouched beside me. Her ears flattened. “He must’ve fallen.”

Wordlessly, cautiously, we picked our way down the slope. It stretched near vertical from where Dancing Tail had stepped right off, and I had more than a couple close calls tempting a similar fate.

When we reached the bottom, Dancing Tail was hissing in pain, but alive.

I let relief brush through me before I saw his front right paw. It was twisted. Almost backwards. Broken.

“It hurts,” he said.